Electra has few of the attractions offered by most small Texas towns. There is no shady park, no fountain, no monument, no energetic local café, no hardware store for wandering the aisles. To say that it is a sleepy town — that it is NOT electric — comically understates the obvious. The streets in Electra remain mostly silent throughout the day, and the storefronts off the primary commercial street are either empty or rapidly decaying. However, on the primary street, East Cleveland Avenue, there is a healthy-looking pharmacy — at least its storefront is well maintained. During the heat of midday, however, when I stood across the street examining the building façade, I saw only sporadic activity. From time to time, a single customer would pull up quickly in a sun-baked car, rush in, and then rush out again. Down the way, the Pump City Diner was drawing in some dinner patrons. One might say it was the most animated location in town, but it turned a blank face to the street with windows blocked by enormous, faded photos of the dishes offered within.

Other than these two businesses along Electra’s main street, there were only institutions like City Hall and the Chamber of Commerce, along with a silent, stoic bank. Not a single pedestrian walked the sidewalks, and few cars stirred up any dust. The overall impression to an outsider was that this was something of a ghost town, a place left behind. There are many missing pieces to Electra, and much of what’s still standing is vacant or collapsing. Many buildings have been removed or have crumbled to nothing by themselves. Of the demolished pieces of these streets, former floor plans are still marked by paint or chipped pieces of linoleum on concrete floors, now under the open sky and bleached by the sun. These missing buildings have not become tiny green pocket parks or petite plazas with monuments to local heroes, as one might find in more prosperous towns. In Electra demolished building sites have simply become voids, blank spaces still marked with tracings of what was once here. Short stretches of these streets are still lined with small groups of buildings soon to be removed if they are not quickly stabilized and occupied. Many storefront windows are plywood now or the view inside is obscured by tattered blinds. One of them, not fully covered, allows you to peer deeply within, to imagine how the space was once used, to conjure up for a moment what transpired there years ago.

What captivated me about Electra? Perhaps it was the silence that hung so heavily, almost oppressively; it was as powerfully present as the relentless sun. It’s possible that I felt welcome merely because there was space, it was easy to simply look at the town undistracted by pedestrians and vehicular traffic. There was time, nearing sunset, to reflect and imagine. Late in the day this silence was a relief after my many long drives, with podcasts, loud music, and harsh coffee fueling my driving attention for the long distances between destinations across the Texas prairies.

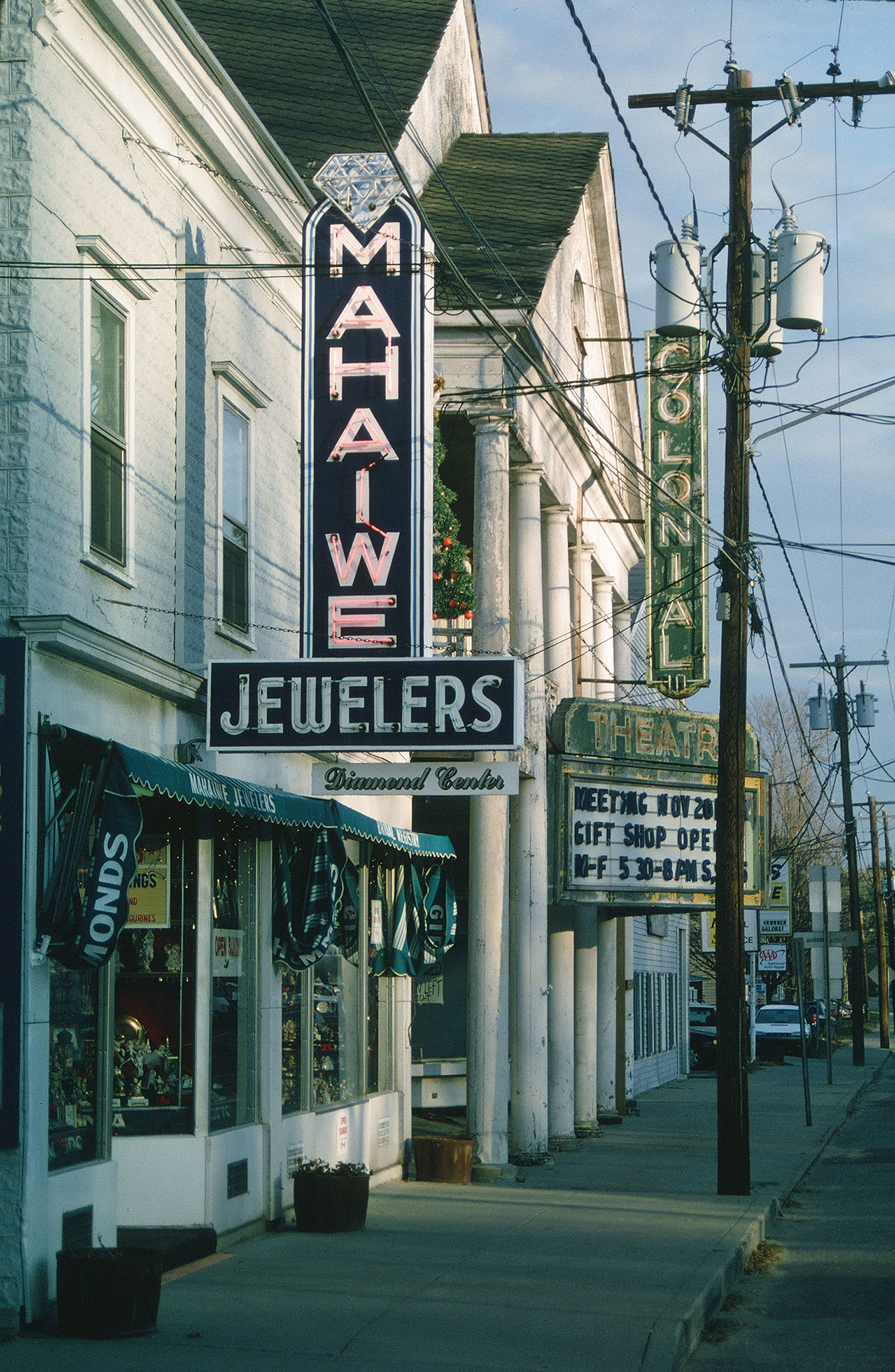

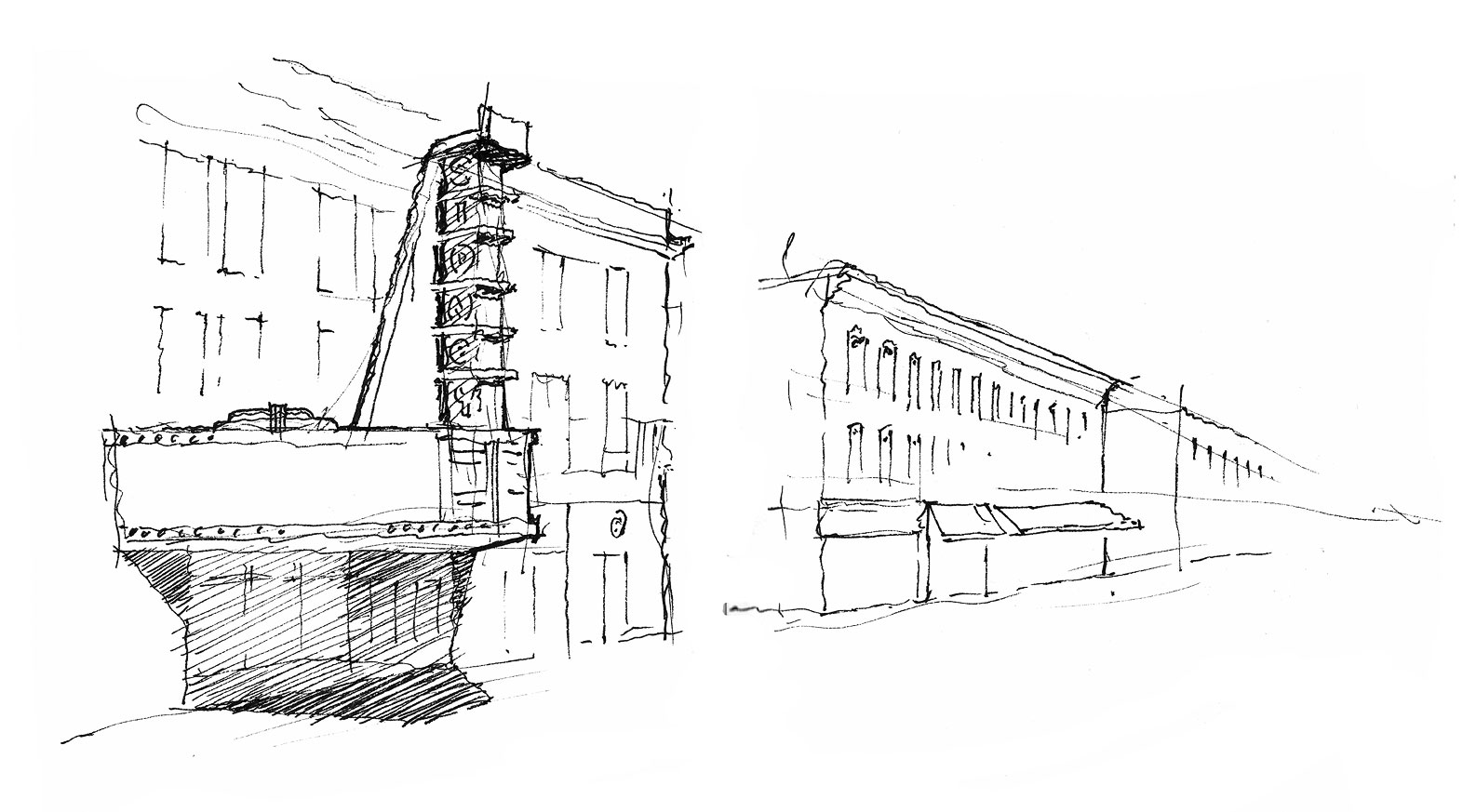

Electra’s primary street showcases respectable, though modest, examples of a regional commercial architectural style that is characterized by simple graphic brick patterns in the parapets of one-story buildings. This pattern of stripped-down facades stands in contrast to the more elaborate ornamentation that is typical of the commercial buildings of most Main Streets of the East and Midwest. A simplicity in commercial architecture developed during a time when the automobile made Main Streets less vertical (lack of upper floors) and more horizontal. This is when this region grew most aggressively, fueled by oil money. Throughout Texas and Oklahoma one can find countless examples of this simple parapet tradition.

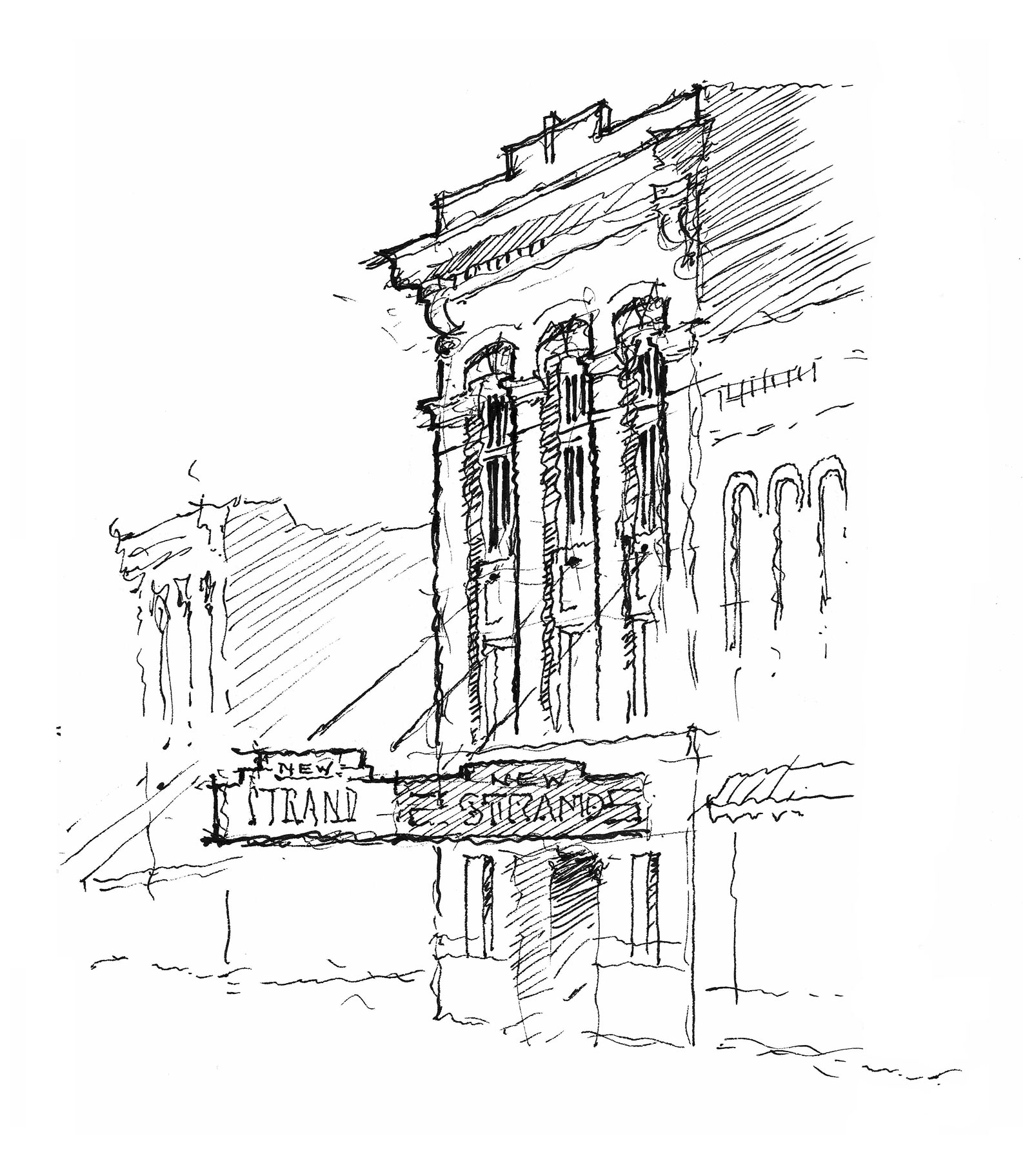

Among the buildings in the fading commercial center of Electra one discovers something remarkably stately and polished. It is epic in its scale and grandeur. The appropriately named Grand theatre stands among the whispered traces of the past, polished and proud, defiantly living in the present. Not only is the building itself in impeccable condition, but its mid-twentieth century marquee appears to be newly-restored. The contrast between this vision of 1920s opulence and the decay around it is dramatic. But this is not Ozymandius, a sad folly toppled by time and surrounded by an endless emptiness of sand. No, this monumental theatre, once considered the epitome of bling, stands firm, commodious, and delightful.

Erected in 1919, the Mission Style façade of the Grand is composed of a sweeping stone arch flanked by two brick towers, a traditional Spanish mission church composition, here rendered with flattened, Deco-style neoclassical flourishes. The large arch deserves particular mention because of the contrast of such a form with the humble buildings around it. The triumphal arch motif was commonly employed in the façade designs of theatres across America until the mid-1920s. Each functioned as a sign of sorts, quickly identifying the nature of the building before projecting marquees became a standard, distinguishing feature. The sweeping entrance marked the threshold from one world into another, from the mundane, everyday context of a dusty Texas Main Street into a dreamland where romance, adventure, and exocticism were portrayed on a large silver screen in a glamorous space like no other for miles around. In this small town, the Grand facade is sublime, out-of-scale, startling. When I first arrived in Electra, I wasn’t prepared to encounter such a spectacle, certainly not among all the unpretentious commercial buildings in this place of whispers, of long-gone businesses and empty sidewalks.

The greatest surprise was the condition of the theatre, impeccable down to the finest detail. The marquee was a key feature that rendered me mute and unsteadied my sense of where I was and the year of my visit. It was so new in appearance, the fragile neon tubes so impeccably restored and maintained. The persons responsible for this vision had apparently made the decision to restore the marquee to its mid-century appearance instead of updating it with an electronic reader-board or refashioning it to appear like marquees from the 1920s, a trend adopted recently in many theatre restorations. This precious theatre made me feel as if I had discovered a wormhole back in time. The silence of the street aided this illusion; there were no audible intrusions that might pull me back to the present.

During a return visit to Electra, a dramatic formation of clouds was building in the skies to the east. Mountains of white, towering billows rose and expanded at the horizon. It was as if Zeus was summoning gods of the heavens to herald some spectacular event. Late day sun lit these formations dramatically, creating a theatrical backdrop for the lonely majesty of the Grand that emphasized its importance within the camera frame. In the foreground of my picture, below the Grand and across the street, were the sunlit concrete floors of a long-lost cafe and other stores. Grass sprouted through cracks in the paving. Like the clouds, nature was having the last word in Electra. The Grand seemed to bridge the gap between the sublime and the mundane, to be something otherworldly planted on earth, a supernatural gift delivered to this forgotten little town.

How can the multi-dimensional spirit and energy and history and potential of a place be captured in a flat photograph? Pictures of places like Electra have the potential to be much more than ironic and nostalgic, or at worst, ruin porn. I photograph Electra (and towns like it) in order to create documents of places of distinct importance at particular points in time. Vivid lighting and creative framing heighten the experience and pull the viewer into the moment. Each image is conceived to obviate the conceptual plane between the spectator and the subject within the frame. I hope with every photograph — the image of the Grand in particular — to draw the viewer into the setting, perhaps enough to feel emotion: awe, delight, fear, or a whole range of responses.

I aim to create a place experience rather than a visual diversion. It is also my goal when aiming my camera and selecting a composition to illuminate something about the story of a place that I have chosen to frame. My presentation of the Grand theatre, enhanced by the mountainous cloud bank, suggests how the theatre was most likely the frontispiece of a grand urban vision in the 1920s, or at least part of a collective hope that this town was going places. The theatre was a symbol of the ambition of its time and place, a product of the sudden explosions of investment in Texas a century ago.

Sometimes the aspirations of the present are conveyed in my work. Cinemas and theatres are currently focal points and symbols of urban renewal, especially for small towns. These buildings, with their architectural flourishes and brilliant signs, are without peer along their Main Streets. They rise significantly above the datum line, above the height and design details of their neighbors. A grand theatre or opera house in a frontier town was once a sign that a community had truly established itself, had risen above the dust, had reached beyond its humble origins to shine on a par with the best towns of the state. Theatres and electric signs helped each town achieve its plans for becoming a White Way, a miniature Broadway. To establish such an image or reputation was once a very real phenomenon, part of the epidemic of boosterism that swept across America during the 1910s and 1920s. My photograph of Electra’s Grand theatre, with its heavenly meteorological setting, seemed to speak to this way of thinking. A century after the completion of the Grand, bold investment and incongruous faith have risen up again through restoration. A phoenix has risen.

When I first encountered Electra, I felt as if I had entered a surreal place, a town so haunted by ghosts and silence that I had stepped backwards, away from the world. Then, suddenly, I discovered this Jerusalemic vision, a heavenly jeweled temple illuminated by golden sunlight. It was impossible to comprehend, difficult to take in at first. But as my imagination calmed, it became clear that what shone brightest was not just the building but a true act of courage and love and faith. The stewards of the Grand theatre had shown tremendous allegiance to this place with an act disengaged from the reality of the context. And I remembered something I often forget: faith is a commitment in the face of a daunting challenge.

I quietly whispered a thank you to the people of Electra and the region for their dedication to this tremendously challenging preservation project and to keeping the theatre alive with patrons. My visit, around sunset, and the hush that greeted me, permitted me to step out of time and feel something great, to let my mind wander and wonder, and to understand what is possible when looking way, way up, and to search within myself about what is most significant in life. It is my hope that through my photographs and writing I can help others to perceive the value and significance of places like the fascinating town of Electra, Texas.