“When Alice finished helping her mother with the dishes she went outdoors and sat upon the steps of the little front veranda. The night, gentle with warm air from the south, surrounded her pleasantly, and the perpetual smoke was thinner. Now that the furnaces of the dwelling-houses were no longer fired, life in that city had begun to be less like life in a railway tunnel…. Other girls sat upon verandas and stoops in Alice’s street, cheerful as young fishermen along the banks of a stream.”

This excerpt from Booth Tarkington’s 1921 novel Alice Adams showcased the American front porch in its days of waning popularity. But the front porch did not disappear: a century later it is still evolving — relocating, and transforming to accommodate changing conditions. The front porch has always communicated the posture of the house and its inhabitants to the outside world, a place to view and to be viewed, a place where personal and social realms are congruent, an observation platform and a stage, a place to show one’s values to the public eye. The front porch is an expression of both civic and domestic values. The porch is about dialog.

As society and cities have changed, the porch has changed in use and appearance. Today’s social media platforms are virtual front porches, keeping citizens inside and in front of their screens, while the real front porch is often staged with whimsical furniture and other props or simply used for trash cans or motorcycles. Or where you go for a cigarette.

Alice Adams’ family could not afford to move to the new suburbs where the air was fresher and the houses were smarter. She resented the “foolish little house” she lived in. Yet her front porch served as a means of escape. Here she and her girlfriends on the street played the roles of both fishermen and bait — another example of the duality of the porch.

The houses of early American settlers employed simple transitional devices from outdoors to indoors: a large, flat stepping stone or a squared log gave access to the front door. Porches were not part of the architectural traditions of the countries from whence these early settlers had emigrated, and the luxury of a porch was not a priority for hard-working pioneers who had little leisure time and tight budgets. In the countryside human and animal enemies lurked in the woods — another deterrent to relaxing on a porch. In the towns of colonial America there were no setback zones where a porch could be placed so here too a simple set of steps led to the front door. Streets were dusty and smelly and you did not want to dawdle.

By the second quarter of the nineteenth century most of the enemies and dangerous animals had been exterminated and porches began to appear, especially on suburban houses and in the countless new communities where leisure time was more plentiful. The wilderness quickly became a safer and more picturesque landscape. New houses incorporated porches and old houses were modernized with new porches. Porches became both fashionable and functional. Emerging architectural styles used porches to enhance the picturesque or monumental presence of the house, and they shaded the interiors and provided cool escapes from hot rooms.

New construction technology during the 19th century encouraged the erosion of the walls that separated the interiors from the exteriors of houses. The introduction of balloon frame construction in the 1830s became the easiest method of building a house. The ready availability of sawed lumber and the invention of wire nails and machine-cut nails (which quickly replaced hand-forged nails) made the nail-hungry balloon frame more affordable. The balloon frame also took less skill to build than timber frame or load-bearing masonry construction. Load-bearing masonry and heavy timber frame construction were not conducive to expressing the plasticity of the skin of a structure or the ease of adding appendages or openings in the exterior walls.

By the mid-1800s illustrated builder’s manuals and other idea books on domestic architecture became increasingly popular. Style and delight were emphasized. In the latter half of the 19th century, a multitude of architectural styles emerged that emphasized the porch as part of the new concept of the house and its relationship to its context. The porch was no longer an add-on but rather an important expression of lifestyle and architectural concept. Through the mid-20th century quotations from historic architecture were imaginatively manipulated to create a new American house. New styles — Greek, Roman, Italianate, Queen Anne, Craftsman, and Modern Colonial and others — all incorporated porches. The porch reinforced the style of a house and engaged it with its surroundings.

Porch life became increasingly important. Leisure time was becoming more plentiful. The porch became a symbol of social fluidity by softening the transition between inside and outside space, welcoming visitors and encouraging the occupants to come outside, serving as a bridge between two realities. The porch enabled both penetration and escape; it embodied the spirit of a nation beginning to see the value of community awareness and hospitality. The porch became visual evidence of a people’s commitment to the conquering of frontiers that had previously separated them from each other and from the natural or built environment.

Numerous authors and architects published books promoting houses with porches. Andrew Jackson Downing (1815-1852) was an American landscape architect, but he is well known for his books that presented designs for picturesque country and suburban houses that honored their sites. His 1842 Cottage Residences stated: “The porch, the veranda, or the piazza, are highly characteristic features, and no dwelling-house can be considered complete without one of more of them.”

The next generation of influencers that promoted the porchified house included Samuel Sloan (1815-1884). His book The Model Architect was first published in 1852; widely distributed, it went through several revisions through the 1870s. A walk today through neighborhoods throughout the US that were built in the last quarter of the 19th century reveals street after street of houses based on Sloan’s examples. His many house designs illustrate how the porch found its way into the American imagination. What he labeled Design VI, An Italian Villa included detailed drawings, plans and even cost estimates for what he saw as a harbinger of things to come for American residential architecture. Sloan’s impressions of Italian villas were inspired by a quaint fairy tale notion of Italy in which picturesque undulating topography delighted the eye from large windows, porches, balconies, and towers.

Residential architecture in the US embraced the porch with even more enthusiasm after the War Between the States. With the growth of more leisure time, summer houses began to appear at new vacation resorts all over the country. Newly-prosperous tycoons built vacation getaways at waterfront and mountain sites across the country. A vacation house can be more daring and innovative in its architecture because it is conceived primarily as an escape from the mundane workaday world. The porch became a way to express an openness of the house to its site and a new way of living in the American landscape. Suburbia also grew at this time. The expansion of cities and towns into new neighborhoods accessible by trolley car (and eventually the automobile) provided larger lots for single houses and the porch reinforced the experience of living in a park-like setting. Towers, verandas, balconies, and generous fenestration opened up the free-standing house to the fresh air and bucolic settings that were becoming increasingly accessible.

In plan and elevation the suburban house was not constrained by a tight urban site where it needed to be attached or tightly placed next to sidewalks or adjacent houses. The new suburban house could be seen as three-dimensional, not just a façade facing the street, and the porch was a device to reach out into the landscape in every direction — a landscape now free of security risks and accessible from Main Street by new trolley cars and other mass transportation.

What became known as the Shingle Style employed wood shingles as sheathing material, a device that further enabled late 19th century architects to experiment with the plasticity of the exterior wall. Characteristic of this style were curving walls, an emphasis on horizontality (that Frank Lloyd Wright further developed), and an interplay between space and structure not previously seen in American architecture. Shingle Style houses were fashionable in resort locations where porches expanded the living space, incorporating balconies, terraces, dining porches, front porches, back porches, sleeping porches, and carriage porches or porte cocheres, a convenience that eventually welcomed the automobile.

By the third quarter of the 19th century more citizens in both town and country were enjoying the views from their porches. For many, leisure time was expanding. People were able to be more open to their surroundings than their ancestors were. An optimism that pervaded many aspects of American life manifested in the front porch. The porch blurred the boundary between inside and outside, visual evidence of America’s commitment to conquering dimensional frontiers, part of a growing national communal spirit. The heyday of the porch aligned with a period in American history (1865-1925) that witnessed unprecedented economic growth. The porch embodied the confidence and openness of a country growing in every direction. The circle of people in a neighborhood now had easy access to each other via their front porches. Local citizens knew each other and could iron out local issues. The front porch is an enemy of big government. Might porches someday be outlawed?

Exposure to full spectrum natural sunlight is regenerative to our metabolisms. It enhances healing and it stimulates the brain and the heart. The porch invites citizens to get outside in the sunlight and fresh air. The “news” on your device or TV is monetized to sell products and fabricated to program you. By interfacing with neighbors on a front porch the real local news can be heard — more reliable than what you see on the TV screen and truly interactive. A nation of neighbors talking to neighbors is harder to control by a government than a nation that gets its news from mass media outlets. The porch is an enemy of a digital control grid. Local community is floundering without active front porches and Main Streets.

The early decades of the 20th century witnessed the increased production of automobiles that encouraged people to explore the world beyond their porches. More time was spent away from the home. The increased traffic speeding by was not conducive to lingering on the front porch. Noise and air pollution were added incentives to taking a ride in the country. The automobile was a new toy and Americans wanted to play and explore.

By the 1920s the porch began to move from the front of the house to the side of the house to escape traffic noise and fumes and to gain more privacy. The side porch became commonplace for the upwardly-mobile middle class seeking a more private perch beyond the scrutiny of neighbors and passersby. Only one side of the porch still faced the street.

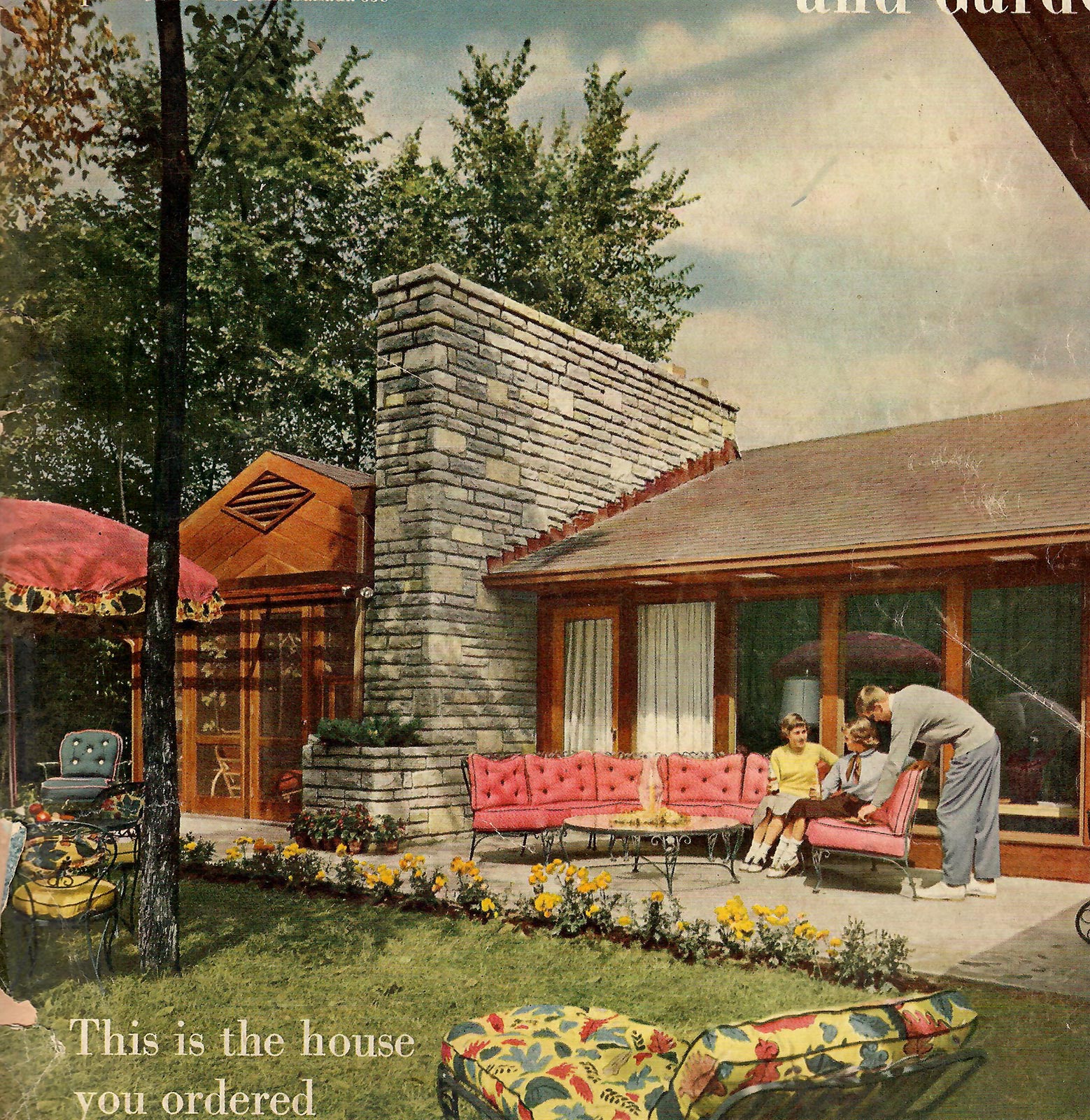

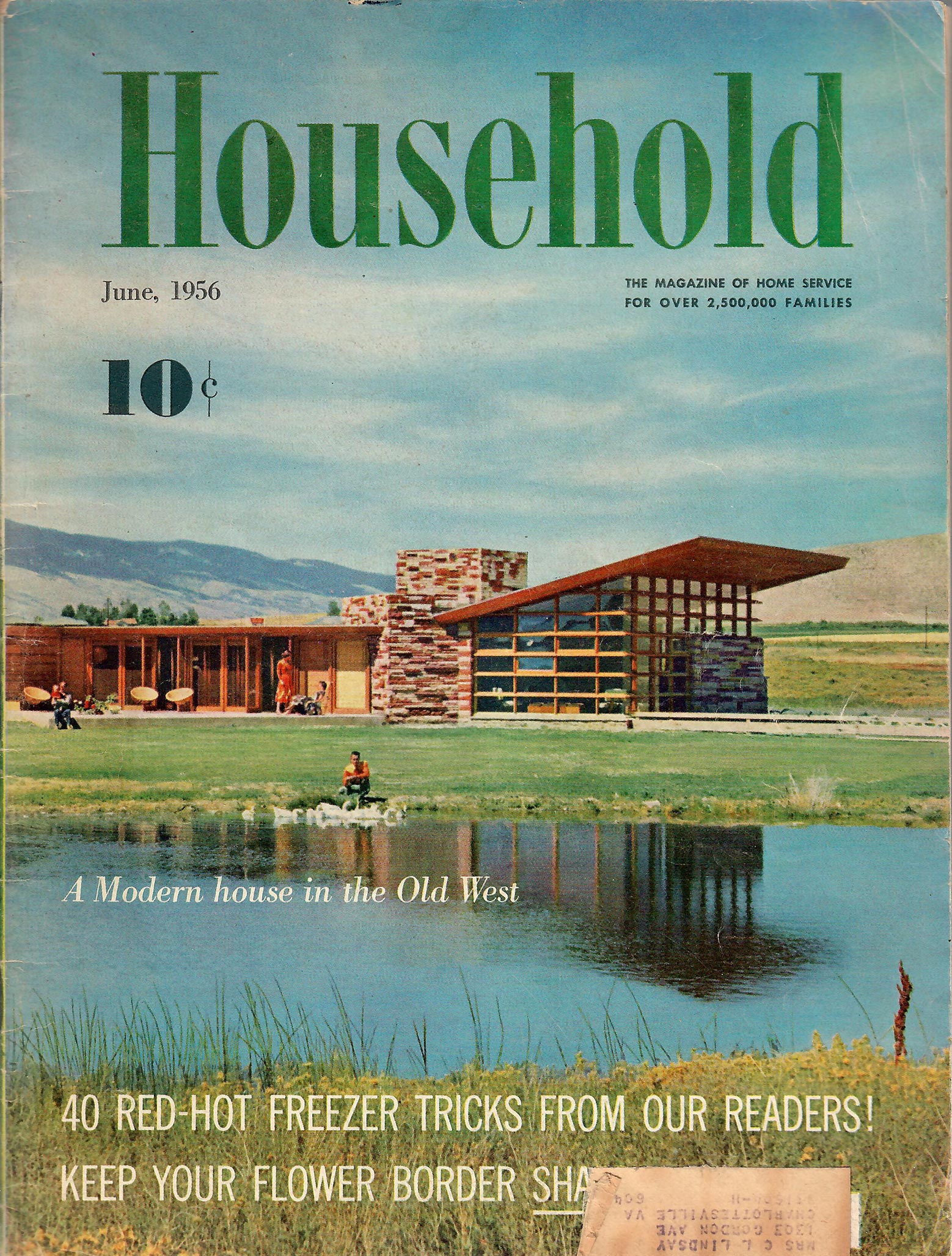

In the 1930s and 1940s the traditional front/side/back porch was losing popularity as the patio began to emerge. Inspiration came from California, where the Spanish courtyard and the Japanese garden coalesced into the Mid-Century American patio. This was the perfect setting for a new lifestyle that was casual, private and suburban. Like the earlier builder’s manuals, magazines promoted the home as a place to enjoy life and express one’s identity. The new patio enabled occupants to get closer to nature since it was roofless and at ground level. This new place – especially if a swimming pool was included — made the house a private resort. By the 1950s few new houses built in suburbia had porches but most had patios of some sort.

The classic American porch did not disappear altogether in the late 20th century. New interpretations included Phillip Johnson’s 1949 Glass House in which the house itself is a porch — but all glassed-in and Paul Rudolph’s mid-century Florida beach houses in which the house was a porch to live in. Across the country the Modern house — with increased use of glass — allowed the house itself to be a climate-controlled porch.

More pervasive today are the neo-traditional houses that use porches to signify neighbor-friendly architecture. Here the porch is designed primarily to be seen frontally in real estate ads. In reality it is often too shallow to be a proper sitting porch. They are just for curb appeal with props arranged to depict a nostalgic setting from a century ago. In modern suburbia today the occupants enjoy the view of their own version of Eden in the back yard or on television nature channels all the while ignoring the outside world.

Countless neighborhoods from the late 19th century — the ones with the great front porches — have deteriorated and are no longer pleasant or safe places to live. Sagging front porches in aging neighborhoods are often left for old-timers and unemployed citizens. Recently, this writer spoke with an elderly lady on her front porch in Lexington, Kentucky. “I just love my porch,” she said, “I’d go crazy If I couldn’t sit out here and watch everything. Now, when the bus goes by I go inside to get away from the fumes, but when they blow away I come out here again and sit on my porch.”

Alice Adams finally did receive the gentleman caller she so longed for and she invited him to dinner to meet her parents.

After dinner “…she went to the front door and pushed open the screen. ‘Let’s go out on the porch,’ she said, ‘where we belong!’ Then, when he had followed her out, and they were seated, ‘Isn’t this better?’ she asked, ‘Don’t you feel more like yourself out here?’