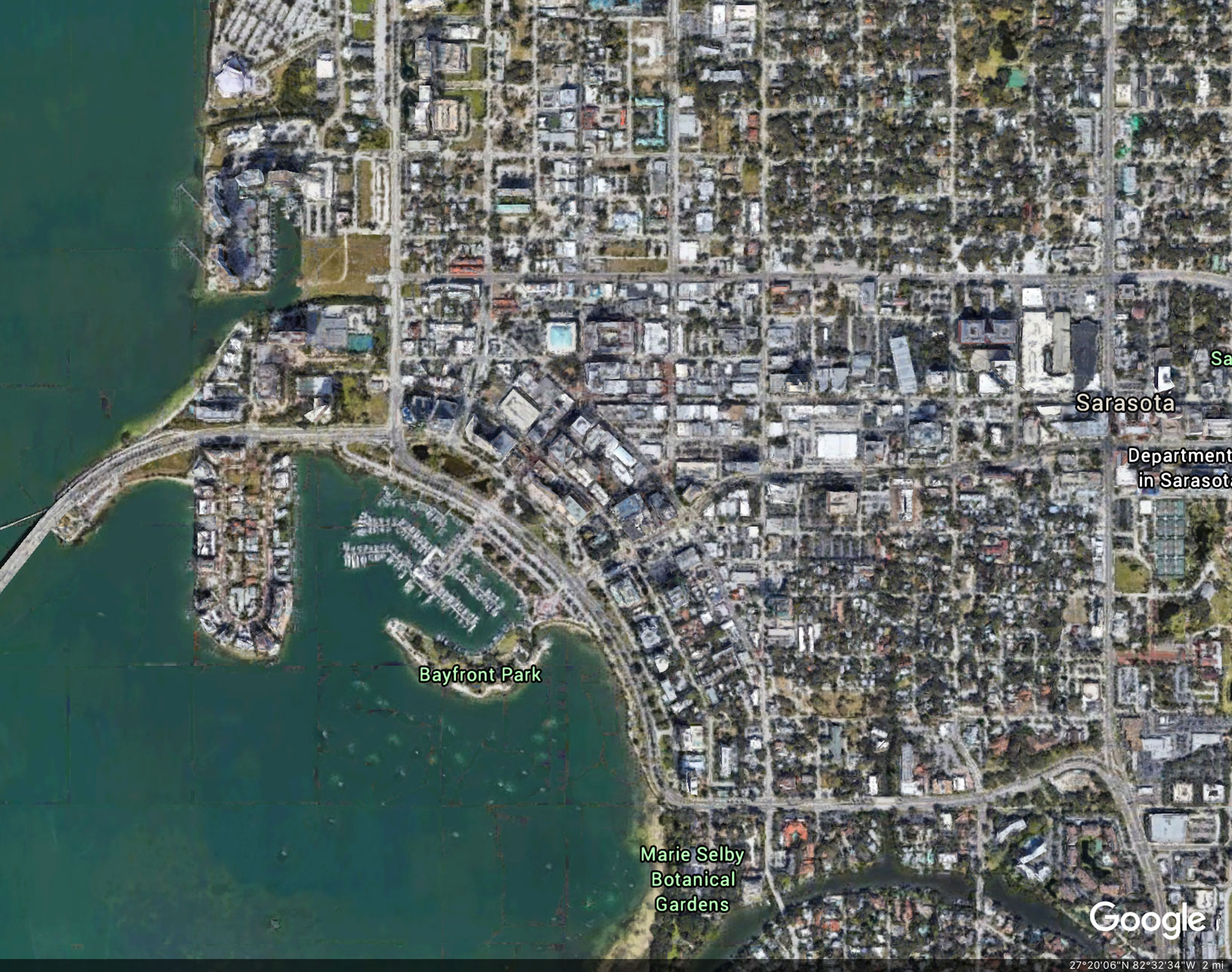

From the air, these days, I travel the United States, studying Main Streets. My vantage point, lofty and analytical, is supplied by Google Earth and other digital tools. This is my means for traveling the country as the world swings back and forth between open and closed during the very uncertain times caused by COVID-19 and civil unrest.

I am safe as I scan from above, and there is much to be gained from solitary, aerial exploration. I learn a great deal about historic settlement patterns, about different arrangements for courthouses and open space within the urban grid, about density and scale. Yet I ponder whether it might be time for me to leave the exile of my desk, brave the ever-changing, risky frontier of America, on the road and sidewalk. I long to be wandering on foot with my camera, my sketchpad, and my notepad.

Looking at the country through the lens of a satellite offers merely frozen images, glimpses from the recent past, from cameras that whizzed through American streets years ago. Months back, as the world seemed suddenly immobilized like that haunting scene from The Day the Earth Stood Still, clocks appeared to stop. We surrendered to the surreal. The entire planet seemed to be in shock. And looking at old satellite images during the months that followed seemed almost like real-time snapshots from the air: stationary cars, pedestrians in mid-stride. But American streets have become progressively animated in the weeks that followed our collective deer-in-the-headlights moment in March and April.

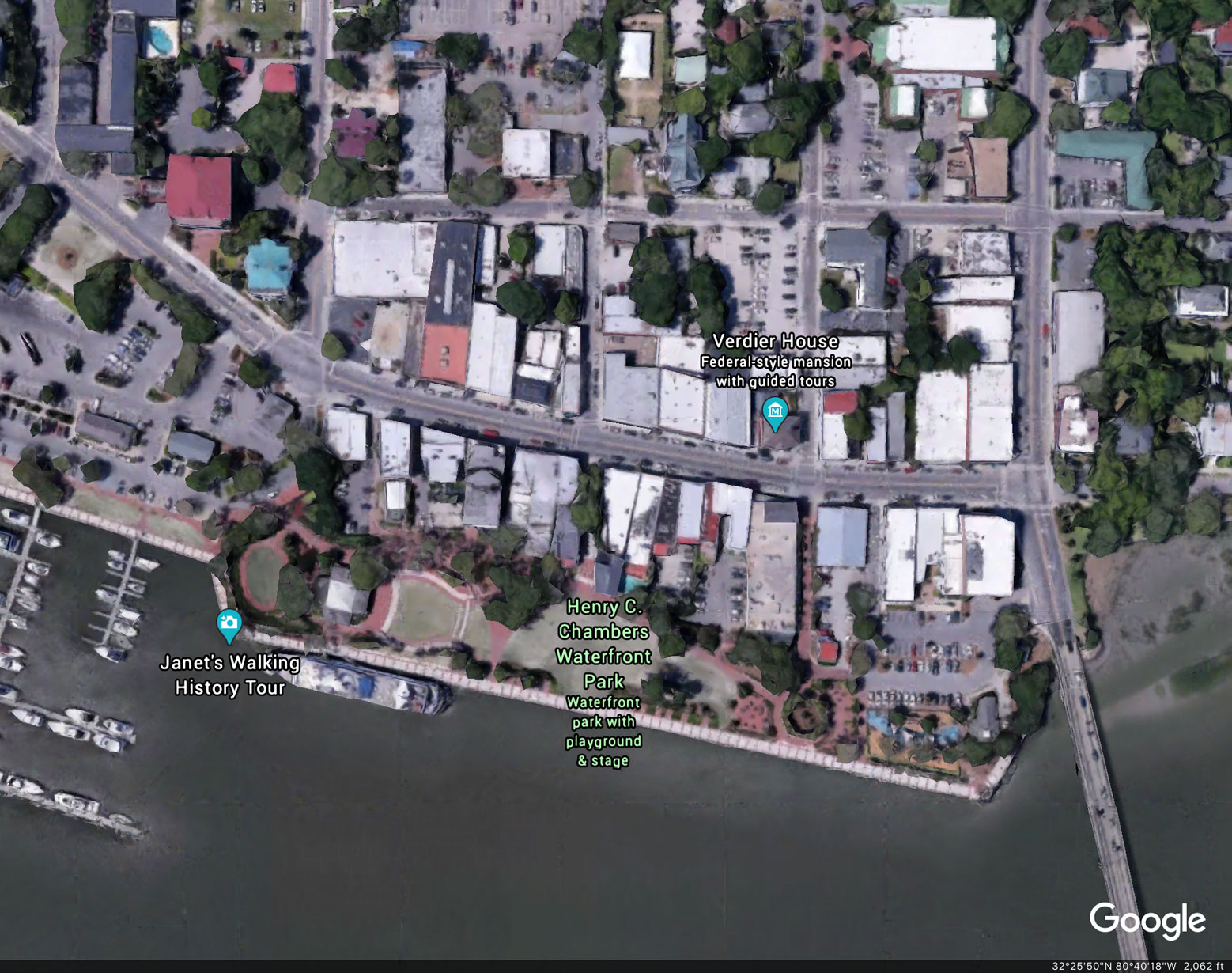

As activity has unevenly ramped up across the country, it has become clear that we need more space, and plenty of it. But not just empty space in the countryside, though many are probably longing precisely for that alone. Safety and solace may surely be found in nature, but the wilderness rarely offers us a sense of community; and in uncertain times, it is often necessary to see others, avow our peace with them, place ourselves around the contagion of enthusiasm and joy. We urgently need more space in our cities and towns, areas shaped by buildings and steps and fountains and shade trees. Main Street has suddenly become more important than ever. It has a significant edge over roadsides, highways, shopping malls, and strip centers, despite the energy and sense of normalcy these everyday places impart.

The central commercial corridor of a town or a neighborhood, with its sidewalks and shops and civic buildings, is a powerful point of convergence. This is typically where commerce and culture and polity meet. Here we can shop and dine, or confer with a librarian, acquire a business loan, or attend a town council meeting. This array of uses super-charges Main Street. And whether or not it is currently vibrant and vital economically, Main Street can still be seen as the agora of modern America (or at least it has the potential to be so). The agora in ancient Greece was the place where citizens gathered for social, political, and mercantile purposes.

To this day, people meet along Main Street or the courthouse square to discuss business matters over a cup of coffee, review pending legislation, or simply buy a hammer. This is a far more effective place to stage a protest or a celebration than waving signs at drivers moving at fifty miles an hour in six lanes of traffic on the outskirts of town. A protest sign has more power and influence held high on Main Street than it does along the highway. This point alone attests to how urgently this public space is needed right now. Throughout American history, all eyes have been on Main Street; it has been the stage for much of our history, both good and bad. From slave-trading to face-painting, the tragedy and comedy of the American experience has been showcased here.

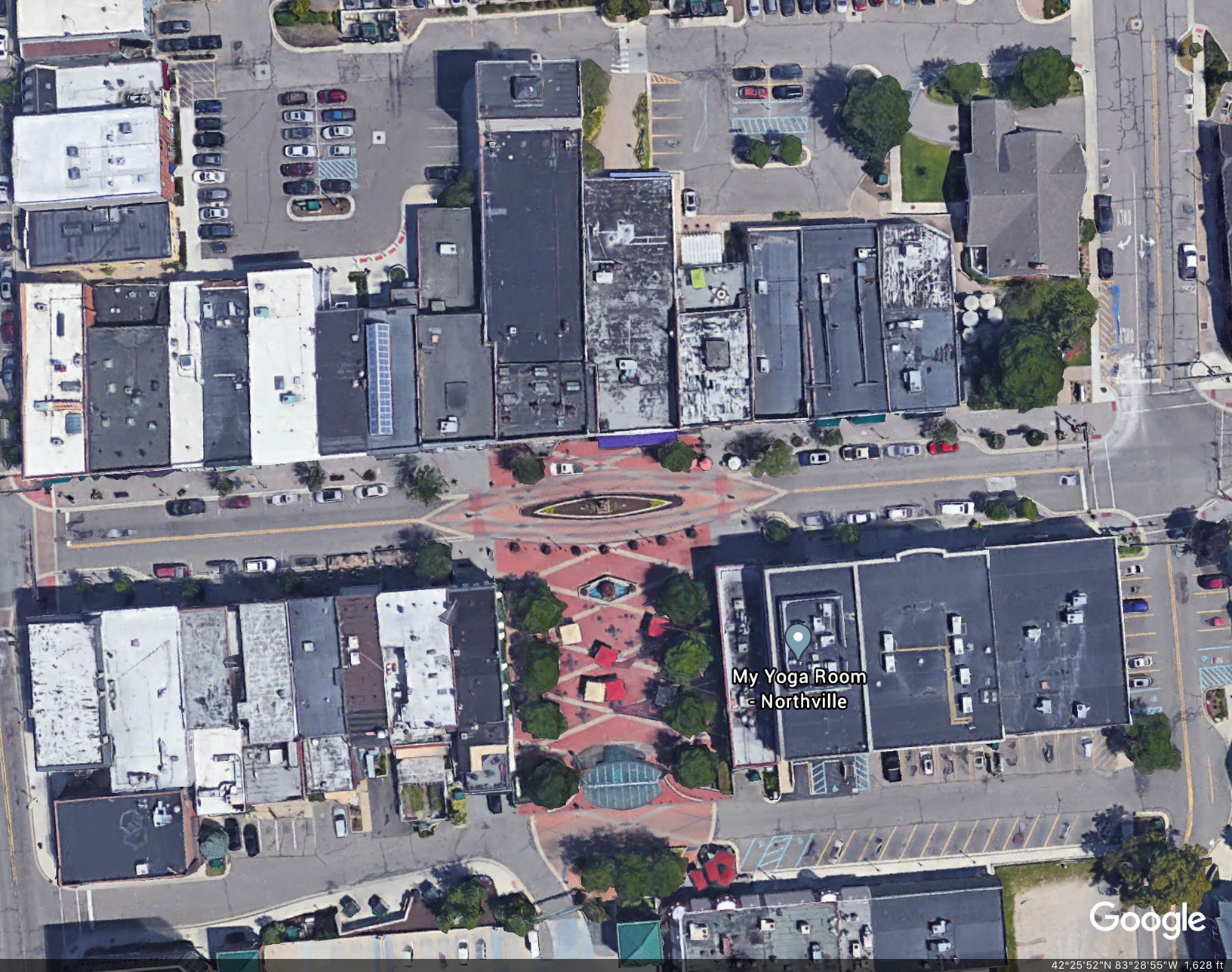

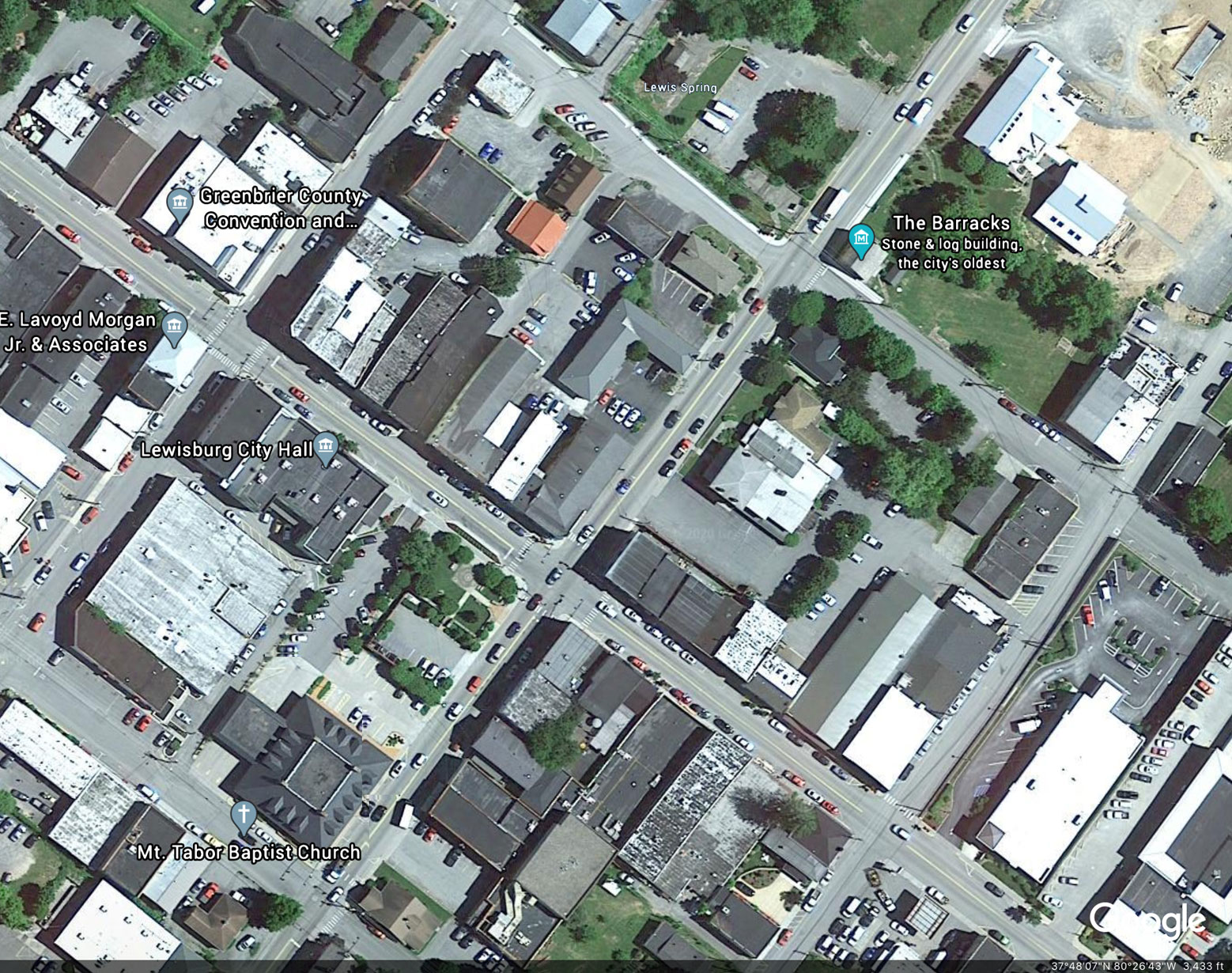

Recent photographs across the United States have proven how effectively urban space like Main Street has been used to persuade the public of the virtue of a cause. Small town urban spaces are just as important as the Main Streets of the mega-metropolis. In many county seats across America, Main Street intersects the courthouse square, which is obviously even more hospitable to public gatherings. Here, linear space blends with a hub, a space created around a focal point (note, however, that business tends to favor the Main Street side of the square). It is worth realizing that marches of protest or celebration cause less traffic disruption in the heart of town than they do on the periphery. The traditional pre-WWII American grid of streets offers a multitude of alternative routes to drivers, a freedom not available when traffic is slowed or stopped along arterial roadways.

Spaces such as Main Street and the courthouse square are charged visually in ways that are completely missing along the commercial strip. They are marked with architectural symbols that convey the presence and importance of civic life. The courthouse, for instance, is often topped with a tower or possibly a dome. In architectural history such a grand form is known as the tholos, which by narrow definition refers to a circular space (usually topped by a drum form or dome). This is a powerful shape, suggesting community, or equality, but also indicating something beyond, a connection to the heavens, a link to a higher power. It reminds us of the importance of working together for great things. Clock towers also suggest a relationship with the heavens, but also the practical matters awaiting our attention on earth. The courthouse also communicates its importance by being elevated above the ground, accessible by broad steps. But wide doorways opening on two or more sides of the building convey accessibility, transparency, even welcome. Space itself is symbolic in the old town, and this is especially true of the space around or in front of the courthouse. This space reminds us of the link between the town and the vast rural landscape beyond. The courthouse square, with its trees and grass, is conceptually connected to the countryside. The courthouse marks the county seat, and its tholos or tower can be seen from great distance beyond the borders of town, a commanding visual landmark that symbolizes its authority over the territory.

Main Street is often the location of the town hall, which is rarely set apart from its neighboring commercial buildings. A prominant classical portico may indicate its special presence, and a clock may be located somewhere on the facade, reminding us of the importance of our time, of our work and other obligations, as well as the potential for the day. The teatro is another form/building typology from classical Greece that makes its way to Main Street, though in a highly modified form. Since the time of the ancient Greeks, the theatre has been a place where moral lessons have been imparted through performance. Choices and consequences play out on the big screen today (or live stage, in some cases) and inform the citizen directly or indirectly. The old movie house has a powerful visual presence along Main Street, appearing as an aberration among generic commercial buildings. The facade aspires to be important, presenting an architectural flourish of some kind, distinguishing it from its neighbors. Older cinemas traditionally employed a grand arch, referring obliquely to the semicircular plan of the ancient teatro, but also more directly to the classical triumphal arch, employed throughout history to mark significant public events as well as entrances to great cities. But it is the canopy marquee, hovering over the sidewalk, boldly beckoning in neon, that tells us most powerfully that this is an important place, and we are encouraged to attend.

As the world opens its doors and tiptoes into places where the public will safely encounter strangers, the forbidden “other” of our hibernation months, Main Street offers the best common ground for re-encountering fellow citizens. Many states have begun the reopening process by advancing outdoor activities first. Restaurants, cafes, and bars, all struggling to prevent financial collapse, are now able to serve tables outside, as long as they are widely spaced. Main Street provides the ideal opportunity for this big step forward. It can reasonably be converted to pedestrian-only use, offering all these businesses space that might otherwise be used by automobiles. One might argue that tables could just as effectively be set up in the parking lot of the local Olive Garden. But consider how well Main Street is suited to give what patrons seek most longingly: the opportunity once more to see and to be seen. The old commercial corridor in the heart of town offers a collective experience, a super-charged space, where the guests of multiple businesses interact. It is only natural that some sort of promenade from place to place would naturally evolve, recharging the spirits of all who partake. The world is still alive, and we share this space, this unique time, despite any division in political beliefs, despite the fear and uncertainty that may still linger from the lockdown and the protests.

This sense of community, of not feeling so alone, can be powerfully generated by the experience of seeing faces near and far, up and down the street, hearing the hum of conversation and distant laughter. We urgently need to employ this magnificent if underused space to its maximum potential. We are sitting on the possibility of filling the street, or at least parts of it. Let life flow beyond the curbs and parking meters. Once word gets out that the Main Street has been fully employed, that the sweet summer air flows generously and safely around everyone, an enormous sigh of relief will flow through town. The power of a shared experience of this kind should not be underestimated.

We are fortunate indeed that Main Street has been waiting for us, is available to be central, if not essential, to our lives once more. Will we get through this trying time, and is Main Street a potential key to our survival? Will the restaurants really stay afloat in the months ahead? Will the county still have anything left in its budget to operate the library this fall? It’s all too early to tell. But if we are to focus our dollar-spending anywhere, I would venture to say that Main Street is where we should do it. I don’t think people really imagine themselves living in the antiseptic bubbles provided by life as lived in an automobile, gathering dinner from a drive-up window, or wandering nervously through a parking lot into the supermarket or the Home Depot, and racing home as quickly as possible. We are justifiably anxious to resume our lives. And yet we need space to do this safely, to avoid backsliding into a new wave of infection. But not just ANY space will do. Main Street, the courthouse square, and the old town center offer the best KIND of space. Main Street was erected more than a century ago to be an outpost of civilization in a formidable and threatening wilderness. This is a powerful thing to remember during these troubling times; it could inspire us to turn here once more for the strength and comfort so sorely needed today.