Main Street is currently suffering an unthinkable setback due to the lock-down and subsequent social distancing mandated by the worldwide COVID-19 crisis. The government-mandated freeze of activity has eliminated customers for any of the local shops, bars, and cafes in most states, food markets and drug stores excepted.

As I write, restrictions on activity are gradually being lifted in places, making possible a slow return to business for some but not all. This is not the first catastrophe to hit the old center of town, our long-cherished but sidelined Main Street; but it most certainly is the swiftest and most unexpected upheaval yet experienced, a true blindsiding. With lightning speed, much of Main Street’s slow climb up from the economic obsolescence caused by corporate big-box stores over the past few decades seems to have been undone. With government policy permitting big-box stores and delivery warehouses to operate as usual throughout the crisis (only because part of their business is selling groceries), it almost seems as if the intent is to squash small, locally owned businesses; the big-box chains are rapidly selling the same books and dresses and chairs that are behind locked doors on Main Street. And since chain restaurants out on the strip have been engineered since inception for curbside delivery, once again corporate America is favored over local ownership; small restaurants and cafes re-worked for curbside pick-up are really struggling to make the numbers work.

It is worth examining, at this point, Main Street’s long history of challenges and setbacks, if only to provide hope that it may survive yet another catastrophe. The fallout from COVID-19 is far from the first major trial for this steadfast street. The growth of train and automobile use introduced perhaps the first major challenges to Main Street’s hegemonic status in America. At one time, each small town or village commercial center enjoyed a “captive audience” of customers. Up through the mid-19th century, village residents and farmers were limited by how far they could comfortably haul groceries and dry goods on foot or by horse. However, once it became possible for trains to take customers easily to other towns, local merchants no longer held a monopoly over their in-town customers. Naturally, food items and heavy equipment were always acquired locally. But discretionary spending could often be accomplished with a great deal of choice. This shopping freedom was accelerated exponentially by the motor car. County seats benefitted initially from the freedom of choice offered by improved transportation. They were magnets for customers because of the large number of merchants gathered around the courthouse square, but also because so much business was generated by government. They were also hubs for rail transport: regional trains, intercity lines, and local horsecars and electric streetcars. As rail and shipping crossroads, they were natural market centers. They provided more than basic sustenance, but increased social opportunities and cultural experiences. Smaller towns began losing population as the nation began its long transition from being a rural populace to becoming increasingly an urban nation, thanks to job opportunities created by the industrial revolution and national food processing, among other phenomena. As early as the turn of the 20th century many small villages that once thrived in the 19th century were merely ghost towns.

But eventually even the county seats were dramatically challenged. Chain stores like the Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company (the “A&P”), J C Penney Company, Sears, Roebuck and Company, and F. W. Woolworth were the first signs of a new momentum that would threaten local merchants for decades. Ironically enough, most of these corporations were born and gestated in smaller to mid-size county seats. That’s where business could thrive in the late 19th century, and that’s when the menace began. By the first decade of the 20th century, most of these chains were well established. The edge they possessed over the locally-owned stores was the ability to buy in bulk and then pass on a significant savings to customers. By the 1920s, local and national editorials frequently discussed how great this threat had become; citizen groups were formed to discourage buying from such establishments.

Post-World War II retail trends required more floor space for retail and prioritized the automobile, and thus the trend toward development outside of the old town center began in earnest. This favored chains, but did not exclude local business. At first, modest establishments just out of the town center were built, each providing space for less than a handful of merchants and a small area for cars to pull off the road. But then large shopping “plazas” were developed farther out, with vast fields of parking. And, of course, the ever-present one-off drive-in restaurant made its way to small-town America, modeled after successful auto-oriented dining long-established in sunbelt cities like Los Angeles and Houston. Such an establishment was usually the unique creation of a local proprietor, and it ruled the town for perhaps a decade or so before the likes of McDonald’s muscled in. The same auto that helped county seats draw customers from smaller towns, leading to their economic demise, now made regional shopping centers possible, offering even MORE selections than did the shops around the courthouse square.

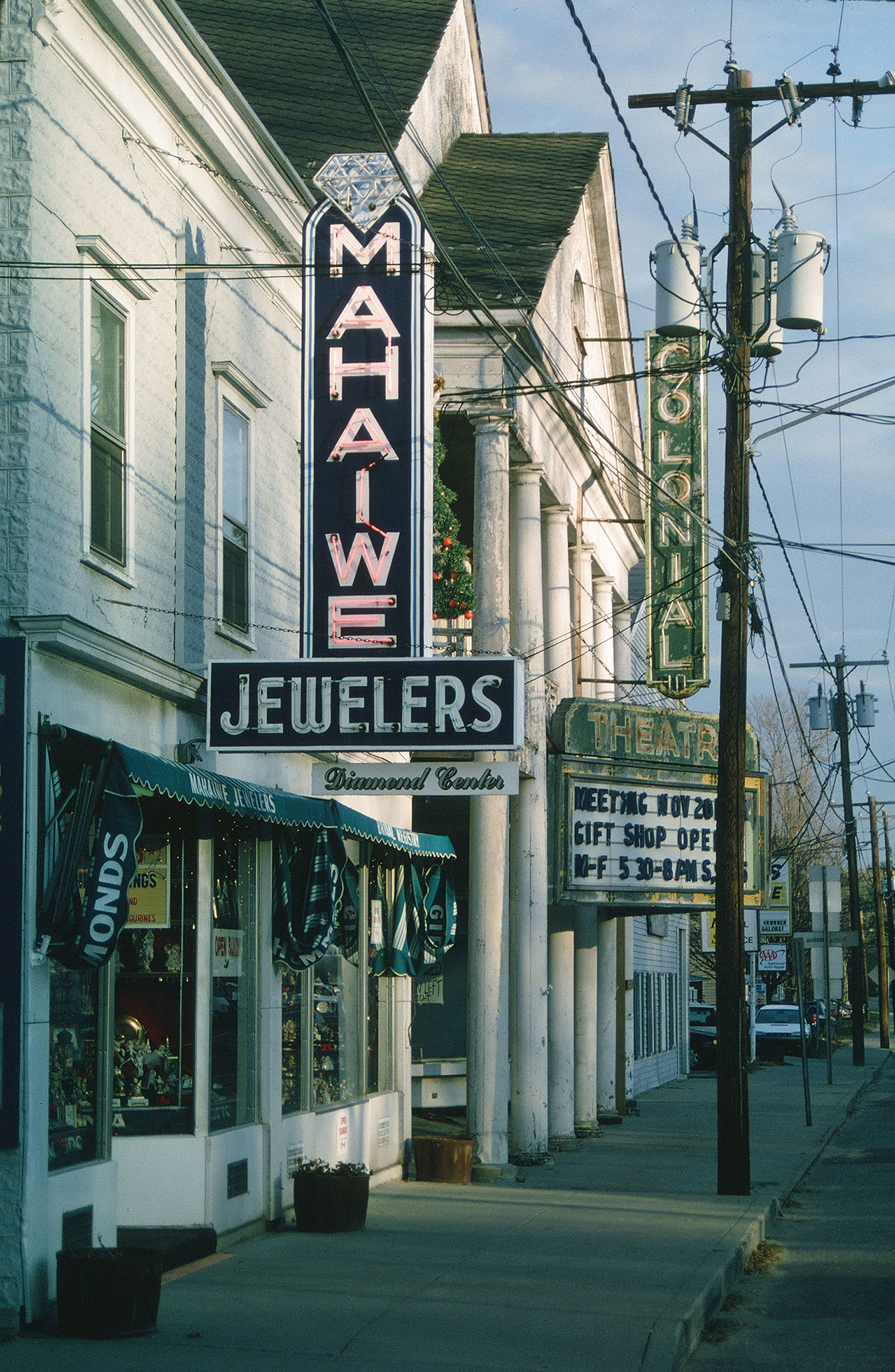

By the early 1970s, many small towns with strong leadership attempted to compete with the new local and regional shopping centers. This effort to help Main Street followed loosely on the heels of ambitious programs launched in the mid-1950s by big cities responding to the steady decline in customers for once-powerful urban retail magnets like State Street in Chicago. Often the plans aimed to emulate the superficial attractions of the new shopping developments. Continuous metal marquee awnings were mounted over shop windows up and down Main Street. Older facades were often covered with aluminum panels in a quick effort to modernize. But perhaps the most startling visual effect was not an addition but a subtraction. Projecting signs were eliminated en masse, either through direct ordinances requiring swift removal or by way of amortization schedules with imminent deadlines, thus quickly encouraging merchants to substitute grand neon store identities with cheap, plastic replacements fastened flat to storefronts. The desired effect, all things considered, was UNITY. Instead of allowing each business to shout for attention, Main Street aimed for an atmosphere of serenity, something like the new malls being built everywhere. In all honesty, Main Street was rather brutally altered, and the benefits were fleeting. It was difficult to compete with corporate America. Few big chains were interested in the smaller spaces available in 19th century buildings, so corporate retail mostly avoided Main Street.

By the 1990s, Main Street realized that competing with shopping centers by aping them was leading nowhere. So an about-face occurred, assisted by agencies such as the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Instead of hiding history, small towns everywhere decided to MARKET history. Main Street uncovered its older buildings and used the architecture to its advantage. Increasingly the market for Main Street was composed of visitors. The influence of Disneyland’s Main Street has been discussed at length by authors like Miles Orvell and Richard Francaviglia, work I recommend highly. The National Trusts’s Main Street program offered its own bias as it aimed to guide restoration while simultaneously coaching businesses in practical matters. These are forces, among others, that explain why many Main Streets appear the way that they do today. To put it crudely, the result is a sanitized, radically edited version of history. However, in defense of the various Main Street programs, it must be said that their strategy has helped many businesses stay afloat. And commerce must thrive in order to keep buildings in good repair. Main Streets are being shepherded to future generations, where conditions will hopefully be more favorable and respectful.

In the early 1990s, as I began studying the architecture of America’s Main Streets for my book Signs, Streets, and Storefronts, small-town shopfronts everywhere were peeling away ill-fated efforts to modernize from earlier decades. The new strategy of leveraging history was well underway when a new bomb hit town, square in the middle of courthouse square, so to speak. County seats everywhere were targeted by a mega-merchant enjoying a meteoric ascent over America. No plan had yet been so carefully (or diabolically) aimed at the healthy market enjoyed by county seats, the very market made possible by the train and automobile when these civic hubs sucked the life out of the smaller towns around them. I will describe the battle as I experienced it visually along Main Streets across the United States in my next essay.

Main Street survived a true economic Hiroshima in the 1990s and early 2000s. It is worth considering that fact, today, as businesses everywhere contend with the loss of customers because of the recent pandemic and civil unrest. Ponder the profound resilience and potential of the historic city center, both big and small. Main Street is still standing, defying all the odds. One need only travel America in a few month’s time to see the slow but steady reemergence of a determined survivor.